Achieving Recursive Blocks in Wagtail Streamfield

Introduction

It's not obvious from the Wagtail documentation that it is possible to build recursive blocks. Building on previous articles here, we can make use of the undocumented local_blocks attribute to build recursion into our streamfields.

This article will take a first, quick look at recursive classes in Python by using a simple file system example. We'll move on to discussing how we can achieve the equivalent in a Wagtail StructBlock using the same file system example to illustrate the concepts.

Before starting on this article, I recommend becoming familiar with the StructBlock local_blocks instance variable covered in these articles.

Building Recursive Classes in Python

I'll start off with a brief introduction of recursive classes in Python. To keep things simple, we'll take a basic file system analogy where everything (ignoring disks and sym links) is either a file or a folder, each folder is a collection of files and child folders.

The File Class

We'll start with the File class and keep it simple - just a name and byte size:

from typing import Self

class File:

def __init__(self, name: str, size: int):

self.name = name

self.size = size

def __repr__(self):

return f"File({self.name!r}, {self.size})"

def __str__(self):

return f"{self.name} ({self.size} bytes)"So to instantiate a File:

file = File('notes.txt', 200)The Folder Class

For the folder class, we include an add() method to add child files and folders. Note that this method has typing to indicate that it takes either a File or Folder as argument. We'll also add a list_contents method to show how we can use recursion to "walk" the folder contents.

class Folder:

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

self.children: list[File | "Folder"] = []

def add(self, item: File | "Folder") -> Self:

"""Add a file or folder to this folder."""

self.children.append(item)

return self # allows chaining

def list_contents(self, indent: int = 0) -> None:

"""Recursively print the folder tree."""

print(" " * indent + f"[{self.name}]")

for child in self.children:

if isinstance(child, Folder):

child.list_contents(indent + 1) # 🔁 recursive call

else:

print(" " * (indent + 1) + f"- {child.name} ({child.size} bytes)")

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return f"Folder({self.name!r}, {len(self.children)})"

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"Folder({self.name}, {len(self.children)} items)"We can now add files or filers, either directly and using chaining, or creating instances and adding those to the parent instance:

In [1]: r=Folder("root")

In [2]: r.add(Folder("docs").add(File("index.txt", 40)))

Out[2]: Folder('root', 1)

In [3]: subfolder=Folder("images")

In [4]: r.add(subfolder)

Out[4]: Folder('root', 2)

In [5]: img=File("sunny.jpg", 1024)

In [6]: subfolder.add(img)

Out[6]: Folder('images', 1)

In [7]: r.list_contents()

[root]

[docs]

- index.txt (40 bytes)

[images]

- sunny.jpg (1024 bytes)The Folder class models a tree of folders and files, and shows how recursion works on such nested structures.

Key ideas:

- A

Folderhas a name and a children list. - Children can contain

Fileobjects (leaves) or otherFolderobjects (subtrees). This is a recursive type: a Folder can contain Folders. add(item)appends aFileorFolderand returnsselfso you can chain calls(root.add(Folder("docs")).add(File(...))).list_contents(indent=0)is recursive: It prints this folder’s name and contents with some indentation.

It loops over children:

- If the child is a

Folder, it callschild.list_contents(indent + 1)(the recursive step). - If the child is a

File, it prints a line for that file (the base case). __repr__gives a short summary likeFolder(root, 3),__str__gives the readable representationFolder("root", "3 items").

Typing notes:

children: list[File | "Folder"]uses a forward reference ("Folder") becauseFolderisn’t fully defined yet.add(...) -> Selfmeans it returns the same type as the class (Python 3.11’styping.Self).

Example flow:

- The recursion stops at files or empty folders.

- Indentation increases on each recursive call, producing a visual tree.

Recursive Blocks in Wagtail's Streamfield

How can we make use of this in Wagtail Streamfields? The standard and documented approach to create child blocks is to add them as class attributes of the parent StructBlock class. Doing this means the structure is set in stone the moment you start the server.

To achieve recursion, we need to make use the the StructBlock local_blocks instance variable.

Lurking in the initialiser of the BaseStructBlock class (which all StructBlocks inherit) is a parameter called local_blocks which takes a set of block definitions and appends them to the StructBlock's child_blocks collection.

What this means is that you can defer the declaration of the child blocks until the StructBlock instance is initialised. Attributes of that instance can be used in those child block declarations such as conditionally adding blocks or passing parameters into the child block definition.

In other words, declaring child blocks as

- class attributes means the attributes of those blocks are shared amongst all instances of that class

- local variables in the class initialiser means those blocks are specific to the instance of that class.

This might sound like a lot of words just now so let's get down to creating our file system analogy as a recursive StructBlock.

For this example, we'll add links as an additional possible member of the folder class as it illustrates using child streamblocks in the recursion.

For each of the block types, I'll add a StructValue class to render out a representation of that object. It's not a vital part of the recursion, it just cuts down the template code for the demonstration.

We will need to set a maximum recursion depth - without this, Django has a risk of running into a recursion depth error. We'll make it part of the instantiation parameters to allow flexibility on a per-use basis.

Imports

Create a file FileSystemBock.py and add the following imports:

from typing import Final

from django.core.exceptions import ImproperlyConfigured

from django.utils.functional import cached_property

from django.utils.translation import gettext_lazy as _

from wagtail.blocks import CharBlock, IntegerBlock, StreamBlock, StructBlock, StructValueFileBlock Class

class FileBlockValue(StructValue):

@cached_property

def label(self) -> str:

return f"┗━ 📄 {self.get('name')} ({self.get('size')} bytes)"

class FileBlock(StructBlock):

"""

A simple representation of a file with a name and size.

"""

name = CharBlock(label=_("File Name"), max_length=255)

size = IntegerBlock(label=_("File Size (bytes)"), max_length=50)

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{self.name} ({self.size} bytes)"

class Meta:

icon = 'doc-full'

value_class = FileBlockValueLinkBlock Class

class LinkBlockValue(StructValue):

@cached_property

def label(self) -> str:

return f"┗━ 🔗 {self.get('name')} ({self.get('target')})"

class LinkBlock(StructBlock):

"""

A simple representation of a link with a name and target.

"""

name = CharBlock(label=_("Link Text"), max_length=255)

target = CharBlock(label=_("Target"), max_length=2048)

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{self.name} ({self.target})"

class Meta:

icon = 'link'

value_class = LinkBlockValueFolderContents StreamBlock Class

With the File and Link blocks defined, we have all the blocks that can be a member of a folder, excluding the folder block itself. When we reach the maximum recursion depth, only these blocks will be available to choose from. We'll create a base StreamBlock for this to keep the code tidy. In this case, there are only two blocks, but your use case might have many more.

class FolderContents(StreamBlock):

"""

A block representing the contents of a folder, which can include files and links.

This definition is exclusive of Folder so that the final folder layer can contain only files and links.

"""

file = FileBlock()

link = LinkBlock()FolderBlock Class

First the StructValue representation of the instance value:

class FolderBlockValue(StructValue):

@cached_property

def label(self) -> str:

return f"┗━ 📁 {self.get('name')} ({len(self['content'].raw_data)} items)"The FolderBlock class is where we add recursion by defining all child blocks in the class initialisation rather than as class attributes.

class FolderBlock(StructBlock):

"""

A recursive block representing a folder that can contain folders (self), files and links.

"""

MAX_DEPTH: Final = 5

def __init__(self, local_blocks=(), max_depth=3, _depth=0, *args, **kwargs):

if not (0 < max_depth <= self.MAX_DEPTH):

raise ImproperlyConfigured(

f'max_depth parameter must be greater than 0 and not exceed {self.MAX_DEPTH}, got {max_depth}'

)

_depth += 1 # keep track of recursion depth

if _depth <= max_depth: # safety check - should never be false

streamblocks = []

if _depth < max_depth: # recursion: add self only if not at max_depth

streamblocks += [

("folder", FolderBlock(local_blocks, max_depth, _depth, *args, **kwargs)),

]

streamblocks += list(FolderContents().child_blocks.items()) # always add base blocks

local_blocks += (

# define folder name here rather than as class attribute

("name", CharBlock(label=_("Name"), max_length=255)),

# add the content StreamBlock here so it can include self

("content", StreamBlock(streamblocks)),

*local_blocks

)

super().__init__(local_blocks, _depth=_depth, *args, **kwargs)

class Meta:

icon = 'folder'

template = 'blocks/filesystem-block/outer.html'

value_class = FolderBlockValue- Each folder can contain other folders (via recursion), as well as files and links defined in a separate

FolderContentsblock. - The recursion is controlled by a

max_depthparameter, which limits how deeply folders can nest - capped by a class-level constantMAX_DEPTH(set to 5). Note that the depth is zero based so thatmax_depth=0would allow no recursion, whereasmax_depth=1would allow a single recursion layer. - During initialisation, the block increments a

_depthcounter to track how deep the current instance is in the hierarchy. If the depth is still below the allowed maximum, it adds a recursive reference to itself under the"folder"key. - Regardless of depth, it always includes the base content blocks (in this case, files and links) and a

"name"field for labelling the folder. These are wrapped in aStreamBlockassigned to the"content"field.

This structure allows editors to build nested folder trees with rich content, while enforcing depth limits to prevent runaway recursion.

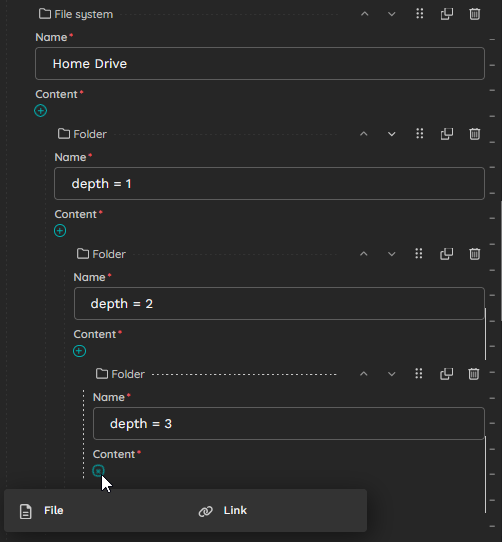

The following screenshot shows a nested FolderBlock at maximum recursion depth:

Note that only File and Link blocks can be added at the maximum depth due to _depth < max_depth being false.

Walking the Recursion in a Template

For this simple demonstration, I will just use an {% include %} statement in the template to call itself to build out the recursive layers. For a more complex object, you might build out a dictionary in a template tag and walk the object that way.

In the FolderBlock, we specified the template path as blocks/filesystem-block/outer.html. As you might guess from that filename, we will need two templates - an outer, wrapper template to seed the node once, then recurse with node only.

Create that outer template first:

{# Wrapper: seed `node` from `self` at the top level #}

{% include "blocks/filesystem-block/inner.html" with node=self only %}Then the inner template:

<div>{{ node.label }}</div>

<ul style="list-style-type: none;">

{% for child in node.content %}

{% if child.block_type == "folder" %}

{% include "blocks/filesystem-block/inner.html" with node=child.value only %}

{% else %}

<li>{{ child.value.label }}</li>

{% endif %}

{% endfor %}

</ul>- The template recursively renders a nested folder structure defined by

FolderBlock. - It starts by displaying the current folder’s label (

{{ node.label }}), then loops through itscontentStreamBlock. - For each child block, it checks if the type is

"folder"—if so, it includes the same template again (inner.html), passing in the child’s value as the newnode. - Using

onlyin an{% include %}tag tells the template engine to pass only the variables explicitly listed in thewithclause—and nothing else from the parent context. - This recursive include allows the template to walk arbitrarily deep folder trees. If the child is not a folder (e.g., a file or link), it simply renders the label inside a

<li>. The<ul>wraps all children, and thelist-style-type: noneensures a clean, unbulleted layout.

This structure enables a depth-aware HTML representation of folders containing folders, files, and links.

For example:

- ┗━ 🔗 Profile (~/profile)

- ┗━ 📄 index.txt (1024 bytes)

- ┗━ 📄 sunny.jpg (2048 bytes)

Conclusion

Creating a recursive StructBlock in Wagtail - like the FolderBlock - offers a powerful pattern for modelling nested, self-referential data structures within StreamField.

By carefully managing recursion depth and dynamically assembling child blocks, we’ve built a flexible system that mirrors a file hierarchy while remaining safe and maintainable.

But the real takeaway goes beyond folders and files: this technique can be adapted to represent any tree-like structure, such as nested comments, organizational charts, expandable menus, or decision trees.

The ability to embed a block within itself opens up rich possibilities for content modelling, provided you enforce depth limits and keep your templates clean and recursive-aware.

Whether you're building a rich content list feature or a multi-layered menu, recursive blocks give you the expressive power to handle complexity with ease.